I feel fortunate to have viewed a most impressive art exhibition last weekend in St. Louis, ‘Paintings on Stone: Science and the Sacred’. Currently, through May 15, 2022, the St. Louis Art Museum is exhibiting a UNIQUE collection of Renaissance paintings from 1530-1800 AD, all painted on precious stone supports. In this exhibition, science and the sacred merge into exquisite art. These rare pieces have been curated from multiple museums and private collections, specifically for the St. Louis Art Museum, and will not travel to any other location. It has been a 15-year project in the making. So if you live in, or can travel to St. Louis prior to mid-May, then put this on your itinerary. You will not regret it!

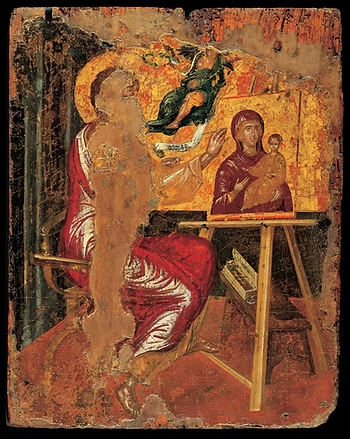

Call me ignorant, but personally, I was not aware that painting on stone was in such vogue during the Renaissance years. I certainly had knowledge of the many fresco works, along with countless oil paintings on canvas, wood, and occasionally copper. But I was very surprised and astounded to see all the amazing works painted on stone supports. By this, I mean alabaster, slate, white marble, lapis lazuli, amethyst, brecciated limestone, agate, onyx, dendritic stone, pietra paesina, and the like. The Renaissance artists in Rome, who pioneered the use of stone supports, took into consideration the stones’ mineral content, color, structure, translucency, and even symbolism, in relation to the themes of their paintings. The practice of stone painting quickly spread to Florence, Venice, Genoa, Milan, Verona, as well as cities in other parts of Europe.

Meshing a Scene with the Stone

What I particularly admired about the paintings in this exhibition was that the artists incorporated the natural pattern, veining, texture, or color of the stone INTO the painting itself. Hence, the unadulterated stone left bare and exposed, may have mimicked clouds, halos, heaven, cliffs, water, storms, caves, or landscape and was intentionally integral to the overall composition. When painting on stone surfaces, the stone’s natural design and the painter’s addition became a single WHOLE. I’ll show you a few examples.

Sometimes a stone background works simply because its presence symbolizes power and wealth. This is evident in a Portrait of Cosimo I de’ Medici (1560), by Il Bronzino, where the porphyry, which has a long-standing association with imperial authority, is left unpainted. The slab on which the portrait was painted was likely sawn from a porphyry column, as the sole porphyry mines, located on the coast of the Red Sea in Egypt, were closed in the fifth century AD. Porphyry, a rare, hard and difficult to cut stone was popular in the Imperial Roman and Byzantine Empires.

In the Annunciation (1602-5), by Orazio Gentileschi, a support of golden alabaster was used to create a light-filled space in which the angel Gabriel descends before the Virgin Mary to announce her coming motherhood. Alabaster naturally has translucent qualities and in its exposed form mimics fluffy clouds and a heavenly realm. Gentileschi also allowed the stone to form the background columns on the right.

A pietra paesina support was used by Giuseppe Cesari when painting Perseus Rescuing Andromeda (1593-94). In his piece, he left a frame of bare stone all around the edges of the composition conveying a sense that Andromeda was trapped at the entrance to a cave.

In David in Contemplation (1611-12), David stoops beside the decapitated head of his rival, Goliath. Here, the artist Orazio Gentileschi allowed the lapis lazuli support to create the deep blue color of the Mediterranean Sea alongside the rocky shore, while the white calcite inclusions added a rippling effect. He even butterflied the stone to create a mirror-like image in the water that can be seen to the left of David’s forearm,

Here, the Flemish artist Wilhelm Schubert van Ehrenberg chose to paint the interior of a Jesuit Church in Antwerp (1668) on a support of white marble. The church, built between 1614 and 1621, was constructed from the same type of marble as the stone slab on which it was painted here. The artist let the white stone with its light gray striations naturally show through in many areas, such as the columns, archways, and floor. In essence, he painted the negative space.

An erotic element is added to Vincenzo Mannozzi’s portrayal of Flora (1640), the Roman goddess of flowers, as she sits half nude against a gray marble background. This artwork appealed to the Florentine court and reflects the passion for stone that prevailed in Florence in the 16th and 17th century. The juxtaposition of the cool gray marble is particularly effective as it contrasts with Flora’s nude skin and the warm coloring of reddish browns and oranges.

Lastly, Antonio Tempesta in Crossing the Red Sea (1610) used a support of salmon-colored brecciated limestone to create the illusion of water, rushing diagonally and dividing the scene, while the natural white patches in the limestone are suggestive of foam. In the painting, some Israelites have fled to safety along the bank at the lower left. Others have taken refuge on the mottled grey outcropping on the lower right. Meanwhile, the Egyptian army can be seen in the center distance, as they are engulfed by a wave of orange sea.

While MY motive to visit St. Louis was specifically to view this exhibition, I couldn’t help but take some time to visit The Gateway Arch. St. Louis Arch, a landmark for the city, is considered the Gateway to the West. The monument is a symbol of the role that St. Louis played in westward expansion during the 19th century. The arch’s majestic shape and size, standing 630 ft tall and 630 ft wide, dominates the western shore of the Mississippi River. I took a tram ride to the top of the arch from where I saw beautiful aerial views of the Old Courthouse Building, the St. Louis Cardinal’s Stadium, and of course the Mississippi River with its many bridges and barges. On a clear day, it is possible to see up to 30 miles in either direction.

An elaborate visitor’s center is located at the base of the arch, which includes a very interesting museum featuring not only detailed information about how the Gateway Arch was constructed but also information about the establishment of the city of St. Louis. The landscape of St. Louis was actually molded several hundred years prior to the arrival of the Europeans in the mid-1700s. The original Mississippian people, the Native American Indians, who lived in the location of current-day St. Louis from 1050-1300 built many mounds in that area. Some mounds were for homes and ceremonial events, while others were places to bury the dead. About 2000 people lived in that “Mound City”.

In 1763, Louisiana’s French governor, keen on spurring trade with the Missouri River Indian tribes, supported the establishment of a fur trading post on the western bank of the Mississippi River. That trading post later became a village and then ultimately a city. They named the city for King Louis IX of France, the crusader saint. Therein was the start of St. Louis. The museum details the fur trade and the Europeans’ interactions with the Native American Indians who were already living in the area.

Looking westward from the small windows at top of the arch and visualizing the vast developed city as far as the eye can see, it is surreal to think back to how the terrain would have appeared just a couple of centuries earlier. The Lewis & Clark Trail, The Oregon-California Trail, The Mormon Trail, and the Santa Fe Trail all had their origins in St. Louis, for it was from there that ‘The West’ was explored and ultimately settled by the Europeans.

In that vein, the museum also provided a sobering reminder of the detrimental ramifications of European settlement and expansion on the Native American Indian population. For many decades the American Indians negotiated with the settlers and the US government over land, seeking to defend their homeland, cultures, and religious beliefs. Despite winning a few battles, the Native Indians were ultimately overwhelmed. It’s astonishing to note that an estimated 9-12 million American Indians lived in North America before the Europeans arrived in 1492. By the end of the Indian Wars, in 1890, there remained only 248,000 American Indians, most of whom were relegated to reservations. The reality is that one society’s expansion and settlement is another society’s demise. This is a very sad legacy.

In summary, my weekend jaunt to St Louis was remarkably eye-opening in several ways. The mid-west city touched my senses both artistically and historically and proved that there are hidden treasures of enlightenment in the most unexpected places. The Renaissance paintings on stone were uniquely exceptional and unforgettable. I encourage individuals who are able, to make the effort to view it, as it is an exhibition that will likely never be repeated.